Decoding Academic Impact: Citation Metrics and Journal Quartile Systems (A Comprehensive Guide 2025)

With respect to academics, publishing an article is not simply coming up with new knowledge it is ensuring that it is recognized, evaluated, and cited appropriately. This is why different citation metrics and journals ranking systems have been developed.

There are tools available for measuring the impact as well as the visibility of a researcher’s work, and these tools are known as citation metrics. As a graduate student or even a newly minted Ph.D, or an established scholar, the metrics are essential to garner funding, institutional standings, and career advancements.

In this blog, we will explain the numerous citation metrics as well as their calculations and significance which includes the more prominent indexing and citation databases like Web of Science and Scopus, as well as their research metrics: Impact Factor, SNIP, SJR, IPP, CiteScore, h-index, g-index, i10-index, altmetrics, and so on. Also, journal quartiles and their effect on the perception of quality and credibility will be discussed in detail.

Citation Metrics: What Come to your Mind?

Other than quantitative metrics, citation metrics are the number of scholarly publications references issued by other researchers which sum up to the work of the researcher, both single and multi-authored.

The citation metrics seek to provide an answer that supports:

How frequently is your research cited?

To what extent is your work accessed and utilized?

What is the approximate overall effect of your publications?

Though no single measure suffices, when taken together, these metrics provide a more holistic assessment of a researcher’s impact.

Common Types of Citation Metrics

Here’s a breakdown of key citation metrics and what they measure:

Total Citation Count

Definition: The total number of times all your publications have been cited by others.

Where to find it: Google Scholar, Scopus, Web of Science.

Usefulness: A primary measure of the attention and scrutiny directed toward one’s work.

Limitations: Fails to consider context, self-citation, and overall value.

Indexing and Citation Databases

As tools which gather, index, and sometimes report on metrics for scholarly literature, indexing and citation databases comprise a collection of citation databases and literatures. They enable the users to find scientific articles, perform citation analysis, evaluate research output, and much more.

Web of Science (WoS)

One of the oldest and most prestigious citation databases collected is Web of Science which is operated by Clarivate Analytics. It provides curated journals coverage along with comprehensive citation networks.

Core elements of WoS encompass the Science Citation Index Expanded (SCIE), Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI), and the Arts and Humanities Citation Index (AHCI).

As for WoS, its strength lies in its rigorous journal selection policies, which are foundational for quality and meaningful impact. It performs citation analysis with detailed precision and exceptional scope, such as in the Journal Citation Reports (JCR), which includes other measures like Impact Factor.

Scopus

Part of Elsevier, Scopus is known to be one of the most extensive citation and abstract databases for peer-reviewed academic literature. Unlike WoS, it has a wider selection of journals, including more regional and open access publications. It does not limit itself to journal articles, as Scopus also includes conference proceedings, books and patents.

Scopus is known to offer many metrics to assess and evaluate the research productivity of departments and institutions, including CiteScore, SCImago Journal Rank(SJR) and Source Normalized Impact per Paper (SNIP). The comprehensive coverage offered alongside the ease of use, makes Scopus very popular among researchers.

Google Scholar

Not as organized as WoS or Scopus, Google Scholar has a very broad index range, as it covers all forms of academic documents like articles, theses, books, court opinions, and preprints. It is free to access and hence is used widely across multiple academic fields.

The h-index and i10-index are part of Google Scholar’s citation metrics and give a glimpse at the productivity and citation impact of individual scholars.

Other Indexing Databases

PubMed: Concentrates on life sciences and biomedical topics.

ERIC: Deals with education-related literature.

PsycINFO: Deals with psychology and related behavioral disciplines.

IEEE Xplore: Provides literature on electrical engineering and computer science.

These databases focus on specific subjects and help to increase the publicity of research in certain fields.

Research Metrics

Research metrics measure the impact, quality, and outreach territory of academic works. Considerable research activities are evaluated with these indicators on journals, single researchers, institutes, and research outputs.

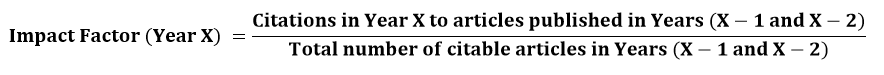

Impact Factor (IF)

Published each year in the Journal Citation Reports (JCR), the Impact Factor is perhaps the most well-known journal metric. It measures the mean of citations an article published in the journal received in a particular year for all the articles published in the previous two years.

Formula:

This measure has faced weakness claims for being too easily manipulable and limited in its time frame for citations.

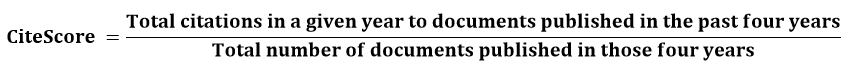

CiteScore

CiteScore is an advanced metric available in Scopus that computes the average journal citations a journal receives over a period of four years.

Formula:

CiteScore is believed to surpass the Impact Factor in transparency and incorporates all types of documents.

Source Normalized Impact per Paper (SNIP)

SNIP is a contextual citation impact measurement from CWTS at Leiden University, which is integrated into Scopus. SNIP weighs citations by the total number of citations in a particular area of specialization.

Advantages

Takes into consideration the varied citation impacts across disciplines.

Aids in journal benchmarking across different domains.

SCImago Journal Rank (SJR)

SJR is a metric developed from the Scopus Database that combines the number of citations received by a journal and the significance of the citing journals. It employs a PageRank-like algorithm similar to Googles.

Key Features

Evaluates journal prestige.

Citations are not equally valued, and JSR of the citing journal determines the value.

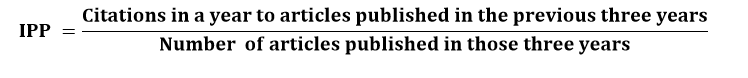

Impact per Publication (IPP)

IPP describes the average number of citations a journal accrues in a year for each paper published within the previous three years.

Its citation window is expanded to three years, which makes it different from the Impact Factor.

Formula

h-Index

The h-index introduced by Jorge Hirsch ascertains both the productivity and citation impact of an author’s publications. An author has an h-index of h if they have h papers each cited at least h times.

Example

If a researcher has an h-index of 15, they have published at minimum 15 papers, each of which have been cited a minimum of 15 times.

Limitations

Ignores the contribution of multiple authors.

Poor reflection of recent productivity.

g-Index

This g-index is advanced from the h-index by Leo Egghe. He introduced it to give greater importance to highly cited articles.

Definition

A researcher has a g-index of g if the top g articles received together at least g^2 citations.

Strength

Better performance for researchers with a small number of highly cited papers.

i10-Index

The i10-index is a designation given by Google Scholar to mean the number of publications by a researcher who has amassed over 10 citations.

Simple but Limited

Measurement can be deemed oversimplistic.

The calculation is straightforward.

Not prevalent beyond the sphere of Google Scholar.

Altmetrics

Altmetrics considers the mentions and references of an article in social networks, blogs, news publications, and even in policy documents that are outside the traditional academic circles. It provides new and current information on what activities are being talked about or done in relation to the research beyond academic bounds.

Common Platforms

Mentions on Twitter

Facebook Shares

Media News

Readers on Mendeley

Blog Posts

Criticism

Can be inflated in reference and usage

Do not measure academic rigor

Advantages

Measured in real time

Immediate attention

Diverse reach

Journal Rankings: Q1, Q2, Q3, and Q4 Journals

Alongside specific citation metrics, the journal’s reputation is equally important in determining how your research is valued, which greatly depends on the quartile ranking (Q1-Q4).

These quartiles are calculated based on the impact factor and citation performance of a journal and frequently appear in Scopus or Web of Science.

What Are Journal Quartiles?

Journals belonging to specific subject areas are organized into ranked quadrants.

Quadrant Description Prestige Level

Q1 Top 25% of journals in a category ⭐⭐⭐⭐ Highest

Q2 Between top 25% and top 50% ⭐⭐⭐ High

Q3 Between top 50% and top 75% ⭐⭐ Moderate

Q4 Bottom 25% of journals in a category ⭐ Entry Level

Illustrative Case: Assume you possess 200 journals from your field of specialization:

Q1: Rank 1-50

Q2: Rank 51-100

Q3: Rank 101-150

Q4: Rank 151-200

Where to Look for Quartile Rankings

These resources will provide you the quartile:

SCImago Journal Rank (SJR)

Journal Citation Reports (JCR) by Clarivate

Scopus Sources

Web of Science Master Journal List

Why are Q1 journals relevant?

Maximum reach and impact

Higher likelihood of citation

More regarded during academic evaluations and funding, and is more value during appraisal.

Typically affiliated with double-blind peer review and other rigorous processes.

Note: Competing for space in Q1 journals can be fierce and often requires submitting highly original, well-structured pieces.

Is it advisable to publish only in Q1 journals?

Not precisely

Q2 and Q3 also contain quality publishing.

Some niche or emerging subjects may fit much better with Q3 or Q4 journals.

Build a robust research portfolio, especially in the early phases of your career.

Getting a paper accepted by a Q1 journal, which sits in the top 25 percent of listings like the impact factor score, is still a dream many academics chase. Such journals promise wide exposure, tough-but-fair reviews, and that extra shine of prestige everyone notices on a CV. When scholars try to land bigger research grants, move up promotion ladders, or simply stake out a solid reputation, a handful of Q1 articles are often tagged as must-haves.

That said, aiming to publish only in Q1 venues is risky and rarely smart for every project. The same pressure that gives a journal its shine can stretch review times, boost rejection tallies, and limit editorial interest to very narrow themes. New researchers, those crossing discipline lines, or people tackling practical, niche questions may actually find faster release and friendlier guidance in Q2 or even good Q3 journals, where quality control is still strong.

Even more, a reader’s real-world influence shouldn’t hang solely on a journals rank. A study that shapes local policy, supports community programs, or explains science to the public may earn far wider credit when it appears in a regional or field-specific outlet, no matter what quartile sticker it carries.

Focusing exclusively on Q1 can also slow the adventurous spirit of scholarship, nudging teams toward safe, predictable topics instead of the bold or offbeat questions that spark true innovation.

To wrap things up, aiming for Q1 spots sounds great, but mixing publications in solid journals from all quartiles-usually the ones that match your goals and audience-works better and lasts longer. In the end, let quality, relevance, and real impact steer the choice of where to share your research.

How are citation metrics related to journal rankings?

Citation metrics such as h-index or i10-index measure your impact personally.

Journal quartiles measure the importance of the outlet per publication.

Publishing in Q1 journals might have a positive influence on your citation metrics, but it is not the only method of shaping a scholar’s profile.

Improving Citation Metrics Along with Journal Selection

1. Recommended Journal: Q1 or Q2 for the given topic.

2. Abstracts and titles should include prominent keywords.

3. Network with and include authors from differing institutions/countries.

4. Defend the research in order to increase recognition.

5. Share papers on social media and academic forums such as

ResearchGate ; Academia.edu; LinkedIn; Google Scholar

6. Publish in freely accessible online repositories (Green OA).

7. Add and update author profiles in:

Google Scholar; ORCID; Scopus Author ID; Web of Science Researcher ID

Citation numbers are a big reason why people care about journal rankings. These numbers show how often papers in a journal are read and talked about across the research world, and they help decide where that journal sits on the prestige ladder. Popular measures like Journal Impact Factor (JIF), CiteScore, SCImago Journal Rank (SJR), and the h-index take a close look at how many times a journals articles have been cited during a set time.

Usually, a higher citation rate pushes a journal further up the scale, so well-cited journals tend to get better scores, earn a Q1 label, and appear in the top 25 percent of their field. To give one example, JIF works by averaging citations for papers published in the last two years; that average then decides how that journal stacks up against others in the same discipline. Analysts keep these scores by category, such as medicine, chemistry, or social science, letting researchers quickly find the most influential journals in each area.

Because high citations usually mean wider reading and stronger reputation, citation ranks and journal prestige are glued together. Journals with eye-popping numbers draw stronger articles, bigger projects, and even more readers, starting a virtuous circle of influence and visibility that is tough for newer pubs to break into.

That said, we still need to acknowledge what these numbers can and cannot tell us. Because citation rates tend to be much higher in fields such as biomedical science, metrics can end up weighting those areas more heavily, and researchers in those fields can pad the count through self-citation. Even a large citation total says little about whether a study is meaningful or useful to society.

For these reasons, citation data remain useful for sorting journals, but they work best when paired with careful, human judgment about how sound and important the research really is.

Restrictions of Metrics and Rankings

• Citation practices differ across disciplines.

• The impact factor of the journal does not reflect the quality of the article.

• Inflated citations or self-citations skew results.

• Impact is seldom accounted for with the use of these metrics, if at all.

• Cultural bias for the English language—non-English work is largely ignored.

Metrics and rankings are everywhere in academia, but they have some serious downsides that people often overlook. Tools like Journal Impact Factor (JIF), the h-index, and CiteScore give us tidy numbers to measure research, yet treating these numbers as stand-ins for real value can oversimplify how we judge scholarly work.

One big problem is how different fields behave. Natural scientists tend to rack up citations faster than scholars in the humanities or social sciences, so comparing their scores really isnt fair. Even within the same research area, English-language journals and big-name publishers usually get the most credit, pushing important work from smaller presses or non-English sites to the sidelines.

A small team that helps a local school or shapes a government policy might post low citation totals yet still do crucial work. Relying only on metrics can cause that kind of valuable research to get overlooked.

When universities lean too hard on rankings, they often let these numbers shape budgets, hiring choices, and who earns a promotion. That pattern can end up widening the gaps between well-funded institutions and those struggling to be seen.

In short, rankings and scores offer helpful yardsticks but should never be the only thing used to grade research. A fair appraisal also calls for careful peer review, fresh ideas, real-world effects, and a strong commitment to ethics.

Conclusion

In this time where there is advanced technology, dealing with research databases and their corresponding metrics is vital in the academic landscape. If one is a novice researcher trying to figure out the best high yielding journals to publish in, or is part of the institution hoping to evaluate its research productivity, then knowing the role indexing databases play with and how the different metrics features is essential.

Though older metrics like Impact Factor and h index persist to be authoritative, ‘more recent’ contenders such as SNIP, SJR, and altmetrics have emerged which capture additional focus that, at the same time, traditional spaces like Scopus and Web of Science are considered pillars in scholarly research. With the advancements Altmetric and Google Scholar work towards expanding the borders of academic investigation.

In regard to the true value of scholarly work, the best way to appreciate it is through a nuanced, multi-dimensional approach, which combines both qualitative assessments and quantitative metrics.

As it stands, the totality of scholarly impact cannot be based off a single embraced metric or database.

Read My Publications or visit my LinkedIn

This article gave me a much clearer understanding of how citation metrics like h-index and impact factor actually work. As someone new to academic publishing, I often found these terms confusing or intimidating. Your explanation made them feel more approachable and showed how they can be useful — but also what their limitations are. Thank you for breaking it down so well!

Extremely well written and very informative article.

A compulsory reading for all research scholars (MSc/PhD) and practitioners in science. Many of the listed items are often asked during interviews and often people are clueless about these.

Pls give me email address of best journal publications

Thank you for your interest! I’ll be sharing a new blog soon on how to find the best journals. Please stay tuned for that post!