Quantity vs Quality in Research Publishing: Striking the Right Balance for Career Growth and Academic Survival (2026)

In the field of research publishing, the discourse around the quantity of output versus its quality will always be present. Even at the start of their career, researchers often receive mentor advice of “Publish early and often”, and “Only submit when the paper is truly ground breaking.” In this blog, the aim is to analyze how to find a balance between maintaining a healthy self and producing paper after paper without losing self-control and without being taken advantage of career wise.

It is a tough question to be asked, and even tougher to answer. this is a common question being asked right now, and the question of whether to quickly publish a lot of papers, versus taking time to publish a few, is not the first of its kind. The debate has been going on for quite a while now, and something of, ` which is better, quality or quantity of paper. The debate, however, has been going on at a time when hiring, tenure, funding, and other support rely on the number of papers published, and their impact` is quickly losing its `buzz`.

For this post, I wish to assist young researchers maneuver through the chaos and find the right path. I will discuss the value and impact of publishing often, versus the inverse scenario of publishing one to a few high-quality pieces; I will analyze the potential career pathways that stem from either choice. Finally, I will outline actionable steps that help achieve equilibrium, allowing for short-term success, while also sustaining career growth in the long haul.

The Pressure to publish (Quantity vs Quality)

There is no denying that academic work is frantic. Tenure tracks, grants, and annual evaluations create the need to start filling out the CV. This is where the ‘publishing or perishing’ mentality starts, leading to excessive paper production with many co-authors, or re-hashing the same data set over and over again with minor analytical variations. This is obviously a short-term game where visibility and citations are concerned, and it may work.

However, in the longer term, a deluge of inadequate papers is, in fact, detrimental. It is no longer respectably understood that papers are citations in a CV; especially with the vigilance displayed by search committees and grant reviewers to identify the evidence of narrow research depth in a collection of marginal papers.

Appropriate Journal Selection

It goes without saying that the journal selection is paramount. There is no doubt that high-impact journals are attractive: their high rates of citations and many influential contacts. High-impact journals, however, come with high rejection rates and are less likely to accommodate lower research quality. Alternative, niche journals may lack the prestige some professionals and universities unconsciously associate with their status. That said, striking a balance between high ‘quantity’ and high ‘quality’, and focusing on journals that are well respected in your field that also publish research of lower quality and impact is the most appropriate.

You must submit excellent work that will not be a paradigm shift in a particular field and that will avoid journals that publish poor work to boost their index.

Crafting the Paper

Consider attempting to write your paper whilst creating an image of how people will remember your paper five years down the line. Instead of stretching your results section by adding experiments to make it longer, be bold enough to refine a few of your better results and discuss them more thoroughly. Pose a succinct research question and develop a story around it. It would be worth it to focus on quality writing since it leaves an even more significant impact than the quantity of papers produced.

Learning from Rejections

Your attitude towards rejection should be more on the positive side; it would give you the realization that rejection is a universal experience. A journal decides to return your manuscript most of the time; always make sure to read the reviewers’ comments not to focus your attention only on the number of reviewers’ stars but to see if there is constructive criticism. Use the rejections to improve your research questions and writing since you should not be using a rejection as the reason to submit a half-hearted revision. A flimsy revision should not be the sole reason why you will be submitting a manuscript just to make sure you tick that manuscript.

In short, the best strategy blends a focused number of strong publications with few targeted, impactful studies that can sustain your career long after the tenure clock stops ticking. Quality when paired with strategic timing, thoughtful journal selection, and resilience in the face od rejections will always outlast sheer quantity in the eyes of committees, funders and future collaborators.

Why the Quantity vs. Quality Debate Matters?

Historically, higher education emphasized originality, careful analysis, and a meaningful contribution to knowledge. But over the decades, easy-to-measure metrics number of papers, h-index, journals impact factors, and citation totals have risen to the top of the evaluation pile. Hiring committees, funding bodies, and promotion panels increasingly lean on these numbers to judge how “productive” a scholar is.

As a result, many early career researchers start to focus on the scoreboard to land jobs and grants. The question is whether leaning on numbers works well over time.

Let’s take a closer look at the arguments on each side.

Quantity: The Drive for more Publications

Why researchers Chase Quantity

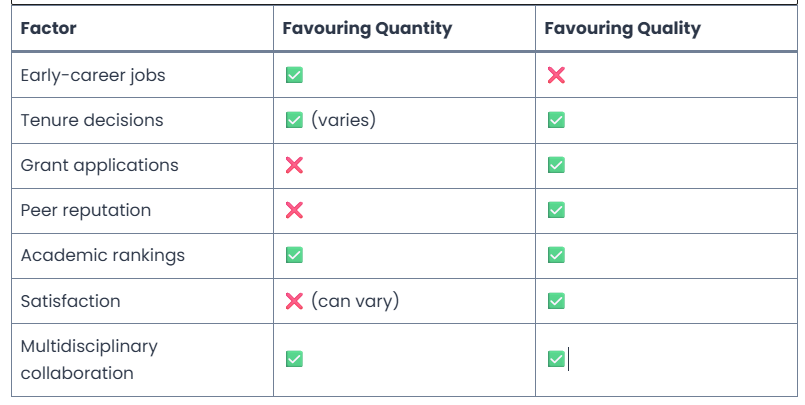

Many academic job ads in emerging economies say something “at least five indexed journal papers” So scholars race to fill that line on their CVs.

The more papers you have, the greater the chance that peer researchers will cite you and want to co-author on future projects.

Colleges and faculties have their own evaluations, and the publications produced are their target, which pushes faculty to keep the numbers published ticking upward.

A mountain of papers can increase the global rankings of an institution and the number of available grants and fellowships they can apply for.

Pros of Quantity

You are likely to get through to more job applications if you have more publications.

More publications can positively affect your h-index and other research metrics that get you attention from promotion committees.

A steady stream of publications can help you get into different research fields and improve your research collaborations.

You improve your writing and peer review skills if you consistently draft, submit, and revise publications.

Cons of Having a Lot of Publications

The more papers you are publishing, the more pressure you will receive and it becomes more draining. It be dulls your creative side.

If you keep publishing papers that are too similar to one another, that might impact the standards and your overall credibility.

Ethical Concerns: Having a primary focus solely on getting as many publications as quickly as possible will lead people to unethical practices. There has been research where people have been accused of salami slicing, where one original study is split into multiple publications and an author sends each paper to a different journal. There is also the unethical practice where authors may cross the line into plagiarism just to boost their publication count.

Quality: The Pursuit of Impactful Research

Here’s why quality matters

In an academic career, as long as you have some publications to begin with, you may be able to land that first job. After that initial job, the publications and work that you have done of higher quality is what is going to keep you in that job for a long time. One publication that is well done, and has citations on it is going to be more valuable than a whole stack of publications that no one has cited.

Exceptional research is going to be the work that is going to be respected and trusted. It’s going to do more than just get published especially by shifting the focus of the research that has been done beforehand, changing the story that is being told by the study, and providing the weakness in the policy that is out and needs to be updated.

Pros of Quality

The best quality research is going to also be research that has longevity, where it isn’t only just one and done. It is going to be the research that for years is going to be cited and build a foundation for other research that needs to be done on that topic.

Field leaders and best quality researchers are not looking for collaboration with someone who just has a high publication count, but is looking for someone who has established a portfolio of quality research.

With more quality research, a researcher is going to get more funding as reviewers are inclined to grant an author more funding the more innovative ideas that have been established in their previous research.

Personal satisfaction: There is a unique kind of satisfaction and pride that comes from producing work that is truly impactful and meaningful.

Cons of focusing solely on quality

Constrained Career Ascendance: Having merely a few publications as a grad student could lead to being removed from consideration for positions or promotions you would have otherwise be qualified for.

Less Esteemed Representation: If you are evaluating a university that is still heavily number-oriented, that evaluation will usually bias against you.

Evaluators Bias: Works that are submitted for review are often criticized for being less flashy or trendy and therefore, likely to be ignored.

Perfection Paralysis: Delays in submission and decrease in quantity of work may be symptoms of an unending quest for the perfect paper.

Campus Experiences

Imagine three different researchers and the ways they handle the quality conversation.

A – The Quantity-First Researcher

Dr. A produces 15 – 20 papers annually, usually in no-name journals with either low or no impact rates. The papers are almost always slight variations of the same work, few people read them, if any.

Outcome: The university promotes Dr. A celebrating their “resourceful output” and organizing award ceremonies, but the big conferences, grants, and funds remain oblivious.

B – The Quality-First Researcher

Dr. B publishes 2 to 3 papers annually, but they are substantive and of high quality. The papers are in top-tier journals and are quickly cited, attracting a revolving collaboration with a few elite in the field.

Outcome: The first few years are slow, but Dr. B gains lasting respect, earns a global reputation, and attracts generous, top-tier funding.

C – The Equilibrated Author

Dr. C publishes about five to seven papers every year and divides his publications to average mid-tier journals with a big one and high-impact papers. Some are initial probes and others create chatter. The pacing also includes teaching and mentoring and also includes grant writing.

Outcome: Career and citation growth rise without a hitch. Tenure and grant renewals are a certainty. This allows Dr C to have a fulfilling and balanced academic life.

These profiles show us while quality is the absolute best to have, the journey is not without big bumps, so paths should be selected wisely.

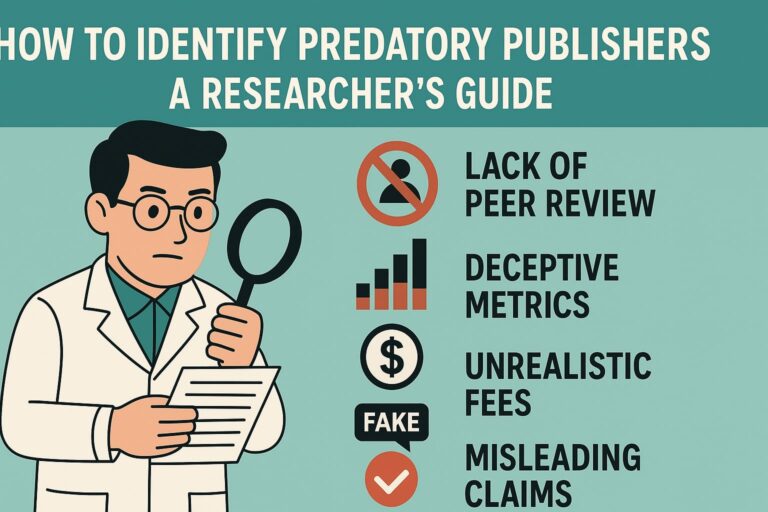

Choosing Your Strategy: Factors to Consider

One’s goals must align with the publishing plan i.e Career, goals, what is required from the institution, personal goals, and changes in the research field. This starts off with questions surrounding what needs to be achieved. Is it tenure, funding, or knowledge dissemination? Each of this has its own distinct publishing target and deadline. This is followed by reflections of the current career status. In the early career stage there is likely a focus on visibility and partnerships, while those in the mid stage target specific journals focused on interpersonal metrics.

Other institutions also have their own demands such as preferred publishers or open access. As a final point, it would help to align with what the field acknowledges as some research disciplines have a preference for specific outputs.

Things to Avoid (Red Flags: When Quantity Becomes Counterproductive):

Publishing a large number of papers from the same dataset, especially if there is minimal difference in the contribution of each paper.

Writing to predatory and low tier journals which are avoided by the majority of the scholarly community.

Unrefined work that is submitted without polishing in order to meet the deadline.

Being dismissive to comments made during peer review and only revising the work superficially.

Things to Help Navigate the Balancing Out:

Smart Targeting: Choose journals that match your work. Don’t just chase Nature or Science, but don’t settle for journals with no readers. Mix medium and high-impact journals based on how new your idea is.

Time Management: Set distinct hours where you can do concentrated research, without distractions. In order to keep a working flow, set time limits to draft and submit your papers, so you won’t lose quality in the end.

Track and Reflect: If you like, you can track your work using ORCID, Scopus, or Google Scholar. Is there growth in your citations? Which papers should you devote your attention to?

Mentoring and Peer Feedback: Participate in a writing group or do a draft exchange with you colleagues. New perspectives are great for spotting errors and you can polish your work without spending too long on revisions.

Journal Expectations and Institutional Bias

A few journals and universities are beginning to appreciate contributions to open science, replication studies, and data sharing, albeit those contributions getting less citations. These contributions are more important for research integrity.

However, there still are places that primarily assess researchers based on their output in terms of the volume of papers. This results in a tension between what the university expects and what research practices is most efficient.

A reasonable strategy is to attempt to meet both expectations: publish enough to keep the institution appeased, but also allocate some time to focus on 1 or 2 papers each year that can really advance the field.

Ethical Considerations

When universities incentivize productivity without considering quality, the following issues may emerge:

Plagiarism, or recycling your own past works without proper credit

Fabrication, or concealing results that don’t match your hypothesis

Misleading co-authorship when CV padding bogus contributions occur

Sending documents to predatory journals that don’t peer review

Ignoring proper data and code usage

When it comes to ethics, they should always come first. Once your reputation is tarnished, it is nearly impossible to fix.

Quality is Not the Same as Perfection

A popular misconception surrounding the production of high-quality works for research is that each and every paper must be a blockbuster for it to ever count. However, this is incorrect and even a well-thought-out process, clear and organized writing, and the paper’s subject directly correlating to your niche in the field is more than enough to label your contribution as a high-quality piece.

Let the goal be clarity, reproducibility of your process, and that the paper be a valuable addition to the field—this is a case where the glamor can be left behind.

A Cautionary Tale for Quantity-Driven Publishing: The Rise of Retractions

A swift increase in retractions, the act of a journal removing a paper, has been noticed, especially in the sectors which are constantly pressured to publish works. Retractions are a clear indication of the results of a “publish or die” situation turning into a “publish or else” situation.

Why Papers Are Withdrawn From Publications

Data Manipulation: Some writers make up fake datasets or alter data in their papers.

Self-Plagiarism: Authors can also get papers withdrawn for recycling their own pieces by not properly citing themselves.

Weak Reviews, Garbage Journals: Articles in these silly journals can get removed if they didn’t get a basic vetting.

Paper Mill: If you try to pad your CV by writing multiple exercise papers from a single study, and from that single study, you could get flagged for replenishment.

The Impact of Retractions

Reputation Destroying: Having your name attached to data that is being retracted could negatively impact your career progress by hindering future job interviews, getting you removed from your academic program, or cutting your funding.

Institutional Disgrace: If you are a university scientist that had to retract multiple publications, the public and your peers will view you as having made poor academic choices.

Trust Erosion: The retraction of a work from a single author with no publication misconduct gives a long shadow. Future claims by the researcher may be doubted, which is difficult to reverse.

Resource Waste: Seals research retraction is a waste of money and resources (time, people, labs, resources) that could have been spent on rational ideas that other people could have used to expedite progress.

Not All Retractions Are Malicious:

People in every field know that it is possible to make a mistake, and that it is sometimes necessary to undo something, but it is not until every one of them goes to withdraw a publication, admits that they have made a mistake, and reverts to a paper that they outline their commitment to transparency.

Transparency is the bridge.

However, a growing wave of poor quality research and insufficient quality control in peer review are likely to turn what used to be the occasional Red Ink Parade of Correcting Novels into something that damages reputation and trust.

Conclusion:

Quality Is the Foundation, but Quantity Builds the House: If you want to do well in the academia, especially if you are just starting, it is necessary to have a reasonable number of published papers. However, do not trade off your ethics, creativity, and deep thinking in the process of getting an extra number.

Think of How:

If you put out quantity, you go on the radar.

If you put out quality, you will get remembered.

If you do it with integrity, the respect will be ongoing.

A researcher with the greatest impact doesn’t choose one over the other, they do both. A successful record captures the essence of the two, including short notes and presentations, as well as multi-paged contributions to journals. This creates a feedback loop. A higher volume of papers opens new doors as an early-stage researcher. Keeping those doors and traversing through them will require sustained effort.

Final Recommendations to Early Stage Researchers

Publish but do it in a timely manner.

Don’t rush to the finish line.

Avoid the metrics race.

Let the impact of your work generate the numbers.

Don’t be afraid to reach out to possible mentors.

Collaborate with those in other disciplines.

Let go of publish or perish. Replace it with publish with purpose.

Read a lot, improve, and extensively revise your writing.

My Publications or visit my LinkedIn