Avoiding Retraction and Rejection of Manuscripts: A Researcher’s Complete Guide (2025)

In the modern academic world, the race to publish grows faster every year. Whether a researcher studies genes, robots, society, or Shakespeare, hiring committees, promotion boards, and grant reviewers still count papers first and everything else second. The old saying publish or perish has never felt truer. Still, getting work out the door means little if it isn’t done honestly, carefully, and with methods anyone can follow. Because of that, two chilling problems haunt scholars of every rank: the dreaded desk rejection and the even worse paper retraction.

Desk rejection is the first big hurdle on the path to publication. It occurs when a journal editor looks over a paper and decides, almost immediately, that it does not deserve to go out for peer review. Fresh authors often feel blindsided by desk rejections because they receive little or no explanation, unlike more detailed feedback that follows a formal review. At many top-tier journals, desk-rejection rates hover between 50 percent and 80 percent, a number that highlights just how fierce the current publishing game has become.

Desk rejections usually happen not because the science is bad, but because the paper misses the journal’s focus, contains unclear figures, is poorly written, or ignores basic rules like formatting. For early-career researchers still figuring out how academic publishing works, seeing a submission tossed back with hardly a glance can feel especially discouraging.

If a desk rejection is painful, a retraction can significantly impact a scholar’s entire career. A retraction formally wipes a published article from the record, telling the community that serious flaws—whether misconduct, mistakes, or ethical problems—make the work untrustworthy.

That visibility can tarnish a researcher’s name, jeopardizing grants, sparking internal reviews, or in extreme cases, even leading to job loss. Retractions typically follow obvious misconduct such as plagiarism or faked data, but they can also result from honest yet giant blunders in analysis or experimental design.

With both scenarios on the table, the pressure to follow guidelines, double-check results, and craft a clear, concise argument has never been higher.

Avoiding desk rejection or a later retraction is about far more than adding another paper to your CV. It’s really about protecting the integrity of science. Public trust in research is already fragile; misinformation, political pressure, and questions over reproducibility push confidence even lower. Given that reality, every scientist shoulder the duty to produce work that is clear, honest, and methodologically sound. High-quality, ethical research increases your own credibility while also shoring up the larger scientific enterprise.

The good news is that steering clear of troubled waters is neither mysterious nor impossible. You simply need a thoughtful plan, solid ethics, careful methods, and clear writing. When you know why papers end up desk rejected or pulled from the record, you can put best practices in place and greatly raise your odds of a rewarding submission.

This short guide aims to provide a step-by-step, no-fuss map for authors at every stage. Whether you are a grad student polishing a first draft or a veteran hunting a slot in a top-tier journal, the intent is the same: spot trouble spots early and replace them with proven strategies. Doing that not only boosts your personal acceptance rate; it also moves us closer to a stronger, more trustworthy, and impactful body of scientific knowledge.

In the publishing game, a manuscript is more than a collection of results; it is your voice, your reputation, and your gift to the worlds research conversation. Treat it that way, and the system will reward you.

As more researchers vie for a shrinking number of journal pages, editors are looking even closer at every submission. Scholars now face two big hurdles on the road to publication: the dreaded desk rejection and the far worse retraction. A desk rejection stings early in the process, but a retraction can tarnish a career for years. Steering clear of both protects your reputation, keeps you on the right side of research ethics, and helps your work gain the audience it deserves.

Understanding Desk Rejection: The First Hurdle

Desk rejection happens when an editor decides not to send a submitted paper out for peer review. Editors often base this call on how relevant the work is to the journal, the overall quality of the writing, and whether it offers new insights or adds to ongoing debates. Because the assessment is quick, authors can hear back within just a few days. Although a desk rejection stings far less than a later retraction, it still pushes publication back and can knock the confidence of early-career scholars. The encouraging news is that almost every reason for being sent back at the desk can be fixed through careful planning, careful writing, and a sharp eye for detail.

Journal Selection

Choosing the right journal is the first line of defence against a desk rejection. A paper that seems solid can still be bounced if it misses the journals scope by a wide margin. To match their study with the right home, authors should read the journals aims and scope, scan past issues, and check that each section of the manuscript speaks to the journals readers. For instance, sending a trial of machine-learning tools to a clinical neurology journal would almost certainly end with a polite but fast no, no matter how strong the methods were.

Adherence to author guidelines

Equally important is sticking to the journals own rules for authors. Many editors say they see the same formatting, style, and length errors over and over, and these slip-ups can sour a first reading. Before hitting submit, writers should double-check that figures are labelled, references follow the set style, and the word count for each section meets the journals limits. Subtle mistakes, like mixing up bold and regular text in titles or leaving keywords out entirely, may look small but they suggest a rushed submission, which hurt the authors credibility.

Almost every academic journal includes a road map that tells authors exactly how to set up their papers: how to format the title page, where to place figures, which reference style to use, and even how many words are too many. Skipping or skimming those details comes across as lazy and can push editors to toss the submission into the reject pile before anyone even reads the science. A careful follow-through makes a lively first impression, shows respect for editorial staff, and genuinely boosts the odds of a yes.

Quality of writing

Clear, grammatically sound writing is just as vital. A paper riddled with typos, jumbled sentences, or muddy jargon gives readers the uneasy feeling the research itself may not have been done with care. This problem hits harder for authors who speak English as a second language, since grammar slips can twist their findings or soften their claims. To sidestep that pitfall, writers should draft slowly, run their text through style checkers, and-or hire an editing service or trusted mentor who knows the ropes of academic English. Investing in clean language protects months of research time and keeps the submission sailing smoothly past early editorial screens.

Lack of novelty or significance

Editors also look for fresh insights; the manuscript needs to tell readers something they genuinely did not know or at least push old ideas farther than they have been pushed before. Research that repeats earlier work without adding new angles or tackling unanswered questions runs the risk of being labeled “interesting but not novel.” Journals want projects that fill a research gap, solve a nagging problem, or shake up accepted thinking, so authors must spell out those contributions up front. When novelty shines through right away, reviewers pay attention and the entire review process speeds up.

Journals expect fresh angles, so work that simply repeats earlier findings or zooms in on tiny, local problems often lands with a thud. Authors must shout the novelty of their study in the title, abstract, and introduction. Pointing out the research gap and showing exactly how the new paper steps in to fill it is the best way to convince editors the work matters.

Ethical compliance

Ethics is never optional. Without proof of approval for human or animal tests, clear consent forms, or a full disclosure of any conflicts, a manuscript will almost certainly bounce. Most respected journals now ask authors to tuck these details-and a note on where data lives-right into the submission. Leave that info out, and red flags pop up, sometimes killing the review process before it even begins.

Figures and tables

Visuals such as figures and tables carry more weight than many realize, so they too have to shine. Each one should be crystal clear, correctly labelled, and looks like it was made by a professional designer. Blurry, pixelated, or-even worse-duped images will annoy editors and hint that the whole project was rushed. High-resolution graphics that show off key results speed up reading and give reviewers an easy way to judge the science.

Step beyond images with a smart, polished cover letter that sets the tone.

Thoughtful and targeted cover letter

Many writers forget that a cover letter is their personal pitch to the journal for their paper. In just a few short paragraphs, it needs to repeat the study’s key findings, say why the journal should care, and mention any ethical guidelines the team followed. When the letter is bland or rushed, it can sour the editors view of an otherwise solid article.

Retractions: A Permanent Stain

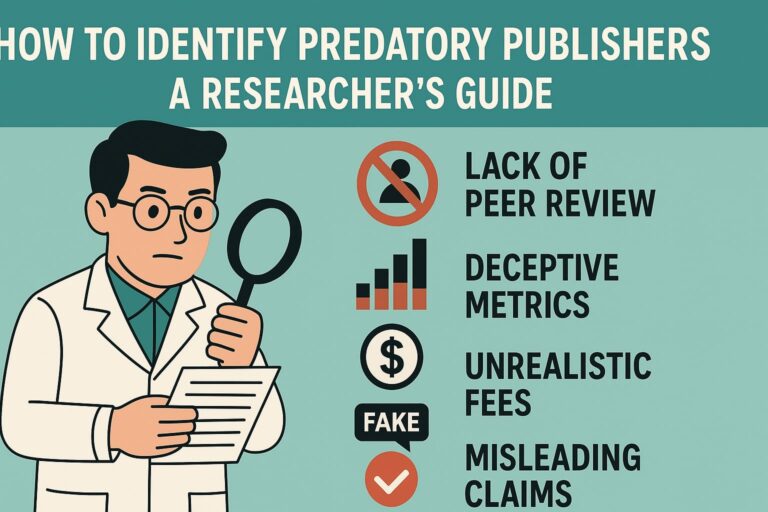

Unlike a desk rejection, which happens early in the submission process and stays mostly out of view, a retraction slaps a paper squarely on the public record after it has already seen the light of day. Because a retraction means officially pulling a work from circulation, it usually points to severe issues: outright plagiarism, fake or tampered data, doctored images, unethical research choices, or crippling problems in the study design. Once a paper is retracted, the mark never fades. Careers have derailed, funding has dried up, jobs have vanished, reputations have taken years to mend, and, in rare but real cases, legal action has followed. For these reasons, every researcher should keep retraction squarely on the prevention checklist.

Plagiarism

Plagiarism sits at the top of the retraction list. Taken at its worst, the offense involves stealing another authors words, data, or even the spark of an idea and passing them off as your own. Copying whole sentences is the obvious trap, but paraphrasing so closely that the original phrasing peeks through can land you in the same mess. Self-plagiarism-potatoes-in-another-potato-sack-is-just-as-bad: that is, republishing your earlier findings without telling anyone. To guard against these pitfalls, run your draft through a plagiarism checker-iThenticate, Turnitin, or even Grammarly-before you hit send. Most journals do their own screening, and even a clean-looking 10 to 15 percent match can trigger a painful review that, if unresolved, ends in retraction.

Data falsification or fabrication

Another serious offense leading to retraction is data falsification or fabrication.Faking research data or making up results that never happened is a serious problem, and it happens more often than many people want to admit. Some scientists feel they have to cheat because of the pressure to publish fast, but the risks blow any short-term gains out of the water. Trust and the ability to repeat an experiment are the heart of science. Break that trust and you spoil not only your own name but also shake the entire community. Because of this, every researcher should keep clean, full records of raw data, analysis scripts, and step-by-step protocols. Honesty and openness are simply non-negotiable.

Image manipulation

Image tampering often causes papers to get yanked, especially in the life sciences. Changing contrast, cropping a bit here, duplicating a spot, or fiddling with pixels to make the data look better is flat-out unethical. Even a tiny adjustment that tricks the reader can end with a retraction. To fight this, journals now run software that hunts for image tricks. That means authors must stash the original files and spell out exactly what editing they did in the paper.

Honest errors

Mistakes that happen by accident, like wrong data crunching, shaky stats, or leaving out a whole chunk of info, can also get a paper pulled. These slip-ups are not as harsh as outright fraud, yet they still hurt a scientist’s reputation and slow progress for everyone. The good news is that many of these honest errors can be avoided. Following strict quality checks, asking colleagues to review analysis, and confirming results with different tests whenever possible make a big difference.

When a published paper is later found to have mistakes, the author’s first move should be to tell the journal. Trying to hide the error only makes things worse. If the mistake can be fixed with a simple correction, the research team should ask for one right away.

Ethical violations

Serious problems like not getting needed approvals for studies involving people or animals can also lead to a paper being pulled. Every project with human volunteers needs clearance from an ethics board and must show that those people gave informed consent. Research on animals has to follow strict rules about keeping the subjects treated humanely. Journals expect to see proof of this in the methods section. Failing these basic ethics can result in retraction and, in some cases, even legal trouble.

Duplicate or redundant publication

Another common pitfall is submitting the same study too many times. Sending one manuscript to more than one journal at the same time breaks long-standing publication rules. So does taking the same set of results and splitting it across several papers without full disclosure. Both actions bump up an author’s citation score without adding fresh ideas to the field. To avoid getting into this trouble, writers must note any reused data up front and make sure every new paper offers a new angle.

Conflicts among co-authors

Finally, fights among co-authors can end in a paper being yanked, particularly when there is clear evidence of ghost authors, guest authors, or any dispute over who really did the work.

Everyone listed as an author on a paper has to follow the rules set by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE). Those rules say each person should have played a big part in coming up with the ideas, designing the study, analyzing the data, or actually writing sections of the article. Talking clearly about each persons role, keeping a record of those discussions, and agreeing on the order of names before hitting send can stop mix-ups and arguments later on.

Respond appropriately to post-publication concerns

Just as authors prepare a manuscript, they also need a plan for what happens after it appears. If a reader or editor spots a question or concern, the honest move is to answer openly and work together. Trying to deny, hide, or downplay a problem usually makes matters worse. Many journals are willing to publish a correction or erratum for a small error instead of pulling the whole paper. Researchers who face up to mistakes in an ethical way often keep their good name even when the article is tweaked.

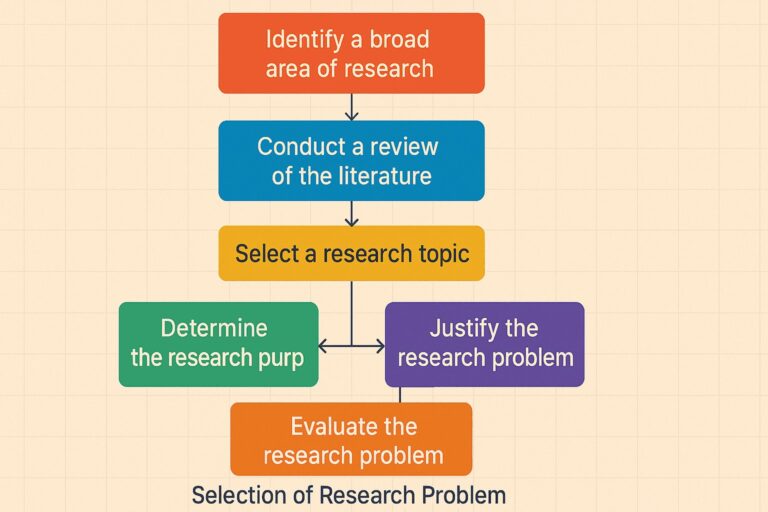

Cultivating Ethical Research Habits

Steering clear of manuscript rejection and article retraction goes far beyond the wording you put in your literary pick-up party; it hinges on a culture of honesty you thread through every phase of your study. The sensible road starts with planning, when you spell out your research question, settle on methods that stand up to outside scrutiny, and spotlight the ethical questions lurking in your design. As you gather data, stick to a written playbook, take steps to spot errors, and store the raw numbers in several safe places so future reviewers can check your work.

When it comes time to write, resist the lure of a quick gout copy-and-paste; give yourself room to draft, let the page sit for a breather, then revise with fresh eyes before sending it out for the peer lads and lasses. A co-author and, if time allows, an outside reader should poke around the text for blind spots. Lean on established checklists like CONSORT or PRISMA to make sure you are not leaving out key bits.

Then you reach submission, a step that deserves careful pacing instead of mad sprinting. Pick, firm confidence, a journal that welcomes your type of inquiry. Build a cover letter that tells the story of your work. Before you hit send, be sure every extra document-the ethics approvals, data-sharing pledges, and any other loose ends-travels with the main paper. Once the study is out, keep your feet on the ground; welcome honest feedback, fix any slips you spot, and keep the conversation going so more researchers hear your findings.

Conclusion

Getting work published in journals is almost never a smooth ride. Its a trip that takes time, hits potholes, and changes course when you least expect it, but grit, curiosity, and a sense of care for your field blow the journey worthwhile. Desk rejections land on almost every author, and they simply mean the paper needs a different home; a retraction hurts deeper and can trail a scholar’s name for years. The silver lining is that serious planning, ethical choices, and a bit of polish on the draft usually keep either blow away.

Every article joins the global pool of knowledge, so errors, weak writing, or hidden biases can spread and shape laws, public trust, and future research in ways the author never intended. Protecting accuracy demands strict ethical guardrails, clear explanation of how the work was done, a willingness to share raw data if asked, and basic respect for editors and reviewers. Good ideas matter, but in academia solid character and reliable methods build a reputation that lasts longer.

Today, tools like A.I.-powered drafting, open-access journals, and data-sharing sites are standard in nearly every lab, raising the bar once more for clarity, honesty, and thoughtful citation. Researchers now must juggle quick deadlines with bigger audiences, and that mix tests both skill and integrity like never before.

When researchers build honesty and ethics into every step of their work, what once looked like a hurdle becomes a sturdy wall that guards against rejection or the bad news of a retracted paper. By being responsible, authors shield their own reputations and, at the same time, help raise the standard the next big study can stand on.

Read My Publications or visit my LinkedIn

Thank you so much Sir, for sharing your top notch tips and real examples in such a simplified and understanding way.

I need a copy of avoiding retraction.

Just read the blog follow the tips given and avoid retraction

Très instructif.

Merci pour ce guide.